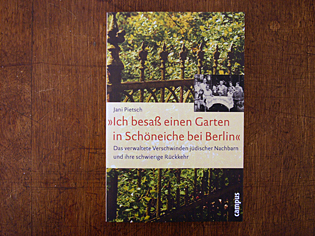

Ich besaß einen Garten in Schöneiche bei Berlin. Das verwaltete Verschwinden jüdischer Nachbarn und ihre schwierige Rückkehr [I owned a garden in Schoeneiche near Berlin. The organized disappearance of Jewish neighbours and their difficult return]

280 pages, Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main/New York 2006.

In 1933, 170 of the 5 000 residents of the village of Schöneiche near Berlin were Jewish. A few years later the Jewish neighbours had vanished, and other people had moved into their homes. Did this go unnoticed? Who organized the disappearance of these people, and what happened to their furniture, their bicycles, and their household goods?

The bureaucratic network organizing the expropriation and robbery stretched from the mayor, the district administrator, and the district council through to the regional president, from the second-hand shop owner and the removal company to the purchasers and the new occupants.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

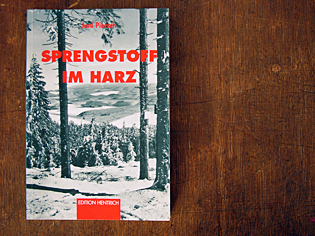

Sprengstoff im Harz. Zur Normalität des Verbrechens: Zwangsarbeit in Clausthal-Zellerfeld. [Explosives in the Harz Mountains. On the normality of crime; forced labour in Clausthal-Zellerfeld]

248 pages, 60 illustrations, Edition Hentrich, Berlin 1998.

Who is interested today in learning that 4 000 Russian and Polish forced labourers had to work in a ammunition factory in the forest of Clausthal-Zellerfeld filling anti-tank mines?

While the threat posed to the drinking water supplies of Lower Saxony as a result of the contamination of the soil in this part of the Harz mountains is a hotly discussed political topic, the history of the people who were forced during the Second World War to work with highly toxic chemicals when making explosives and munitions is ignored. I am not concerned with showing how special such a place is, but rather how ordinary it is.

![]()

![]()

![]()